Thirty five years of investigation in ancient Akhetaten

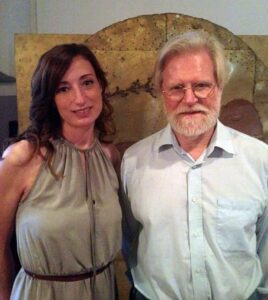

I recently participated in a conference in Bagno di Romagna where the speaker was a truly outstanding personality in the study of Ancient Egypt: Professor Barry John Kemp. I had already had the opportunity to meet him personally a few years ago and can still recall the excitement I felt about our discussion. So, when I learnt that Professor Kemp was due to participate in another conference about the city of Amarna and its people, even if far away from where I live, I decided to go. I could not miss this opportunity. Upon arriving at the event I was delighted to discover that this famous Egyptologist was already there, at the conference room at the Palace. I approached him and even though I already knew how approachable he is, I was still very happy when he was willing to talk again at that moment. I mentioned that I am a staff member of MediterraneoAntico Magazine and that I could not miss the opportunity to ask for the honor of having an interview, to which he kindly agreed. Then I left him to his duty, the conference began and, as foreseen, his stories and images enchanted all the attendees. I went home feeling exhilarated and already thinking about the questions I could ask Professor Kemp. With their excavations at the site of Tell el Amarna (ancient Akhetaton), Professor Kemp and his team have brought to light a number of new archaeological sites, providing new perspectives to the study and understanding of this ancient city. Professor Kemp is an eminent world famous Egyptologist, professor emeritus at the University of Cambridge and Director of the Amarna Project. In 1992 he was nominated a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA) and recently, in 2011, he has been appointed by the Queen of England Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for services to archeology, education and international relations in Egypt (the Order is intended to reward those who have given prestige to the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth in science, economics, art, culture, sports or education). From the reign of King George V, founder of the Order in 1917, this is the first time that this award has been given to an archaeologist.

How did your passion for ancient Egypt begin?

It began at secondary school when I was about fourteen. My father had volunteered to join the British army during the Second World War and was sent to Egypt as a truck-driver in the Suez Canal zone. On his leave time he visited the Egyptian Museum and the popular sites, including those at Luxor. He sent photographs and postcards home to my mother and they became a part of my growing-up. When, much later at school, I was asked to write a project of my choosing, I based it around some of the pictures and began reading books in the local library. In that way did my interest begin, as well as an interest in field archaeology generally.

You have been digging for more than 35 years at Tell el Amarna, the ancient Akhetaton. Before then, where else were your commitments in the world of archeology and Egyptology?

My first research interest was in the archaeology of Abydos, which began when, for a doctoral dissertation (which I never finished), H.W. Fairman, the professor of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, urged me to base it on the extensive unpublished excavations there of John Garstang. I might well have continued to make Abydos the main focus of my research. Around this time, however, David O’Connor chose Abydos as the excavation site for the Pennsylvania-Yale expedition. I joined it for two seasons (1967, 1968). In 1970, at the time when, because of continuing hostilities with Israel, all foreign missions in outlying places were closed, David moved the expediton to Malkata, Amenhotep III’s palace city at western Thebes. I carried out the initial survey of the site and then directed a major season of excavation in 1973. By that time I had become deeply interested in the nature of ancient Egyptian urbanism and the way of life it supported. I carried out surveys of the remains of a number of ancient towns (Kom Ombo, Edfu, Abydos and Memphis), gathering evidence to support the idea that most ancient Egyptians had lived in a fairly close network of towns which were often far more modest in size and building style than seemed generally appreciated.

Why Amarna? And how was the Amarna Project born?

I had been asked to contribute a paper to a research seminar on settlement patterns and urbanisation to be held during December 1970 at the Institute of Archaeology of London University. The seminar resulted in a thick book, Man, Settlement and Urbanism, edited by Peter J. Ucko, Ruth Tringham and G.W. Dimbleby (London, Duckworth 1972). In writing my contribution, ‘Temple and town in ancient Egypt’, I found myself for the first time trying to put into a better order my thoughts on the essential nature of Egyptian society, and how archaeology might be better employed to take the subject further. It led me to realise that the best place to pursue that agenda was Amarna. That paper laid out a programme of work that I have pursued ever since. As it relates to Amarna, along with many co-workers I can see that much detail has been added, and good ideas pursued. But the main goal, which was to quantify the evidence better (the 1960s and 1970s were a time of much optimism in archaeology over the prospects of more precise modelling and understanding of societies) and so to rely less upon intuitive generalisation, has remained elusive. I approached the Egypt Exploration Society to ask if they would support a survey of Amarna, to establish better what had been done and what remained to be done. They agreed. After two periods of surveying (1977 and 1978) they agreed to support excavation, which was at first at the Workmen’s Village. They continued this support until 2006, when a change in UK-government funding priorities led to the withdrawal of the main grant upon which the EES depended for its fieldwork. In order to keep the expedition going, with the help of friends I set up a UK-registered charity (in effect, an NGO) called the Amarna Trust as a means of raising money independently. The EES agreed that the Amarna expedition would no longer run under its auspices. It became an expedition of the McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research (University of Cambridge) though remaining financially independent.

If you look now at the site map of Tell el-Amarna dating from the time of Napoleon and Lepsius, we do not see a big difference between then and today. The remains of Amarna are flat, there are no vertical buildings except for the two famous columns of the temple of Aton. What do you see in the future for this site? I know that a new phase of development of the Amarna Project has been planned and that a reconstruction project is already under way. But what exactly does it consist of? Are you considering rebuilding the ancient temples and palaces in their entirety, complete with pillars, columns, walls…or what are your goals?

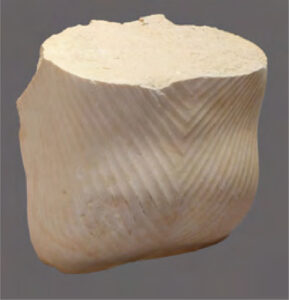

Modern archaeology examines the ground of ancient sites far more slowly than was the case in the first half of the 20th century. Careful excavation and study, often looking again at places excavated in the past, can continue more or less indefinitely. In 1987 the expedition also took the first step in cleaning one of the major buildings, the Small Aten Temple. This led to a scheme to make clearer the outlines of the building in new materials, limestone and mud brick where appropriate. This policy of cleaning and repair has continued, taking in the North Palace, one of the private houses and now the Great Aten Temple. One aim is to make parts of the site more intelligible to visitors. Another is to slow the rate of loss and, in particular (by demonstrating care), to alert the local communities to the importance of the site. Because mud bricks are fragile, whatever we repair in this material needs to be kept under observation and, when necessary, repaired again. As far as possible, the original material is kept visible but sometimes, where walls have vanished, it is necessary to lay a few courses of bricks to show where the walls ran. In the case of stonework, all blocks were removed from their foundations after the end of the Amarna period. But because the foundations often preserve the lines of walls and other features, we lay one or two courses of fresh stones to mark the positions. Apart from the columns at the Small Aten Temple we have not attempted anything more ambitious, which I would consider a mistaken policy.

The workers’ village of Akhetaton is very close in time to Deir el-Medina. Analyzing the site and its findings concerning the daily life of the workers, the hours that marked their days, the construction of their homes, customs, etc. etc., did you find evidence that suggests more differences, or similarities? And how about with that of Giza?

Comparison with Deir el-Medina illustrates the elusive nature of the goal of reconstructing ancient life from archaeology. Most of what we know of the life of the Deir el-Medina community comes from texts: the ostraca and occasional papyri. Papyrus generally does not survive well, even in the desert, and has been an excessively rare find at Amarna. The widespread use of potsherds and flakes of limestone as writing materials was a peculiarity of Ramesside Deir el-Medina, not matched elsewhere in the New Kingdom, including at Amarna. If one were to remove the written material from Deir el-Medina and rely wholly upon its archaeology the result would be a much impoverished picture (as is true for Deir el-Medina itself for the Eighteenth Dynasty). The Deir el-Medina evidence offers powerful and intriguing possibilities for understanding the Amarna Workmen’s Village. Yet one has to hesitate before assuming that the two places worked in the same way. If we had for Amarna the same wealth of written evidence, by now an important question would be to investigate how far Amarna adapted to changed circumstances and how far it kept to long-established practices. As for the Old Kingdom town at Giza, it is so different from Amarna and itself lacks adequate written sources that comparison can only be done at a general level. At the same time, the twenty-five years that Mark Lehner has spent directing work there has provided the only set of data for a large settlement from ancient Egypt which is comparable to Amarna. We (the Amarna Project group) have not yet looked closely enough at the comparisons which can be made.

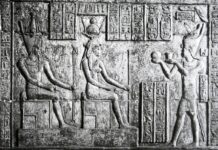

The hundreds of tables of offerings found within the sacred enclosures and temples seem almost an obsession given their large number. Why do you think this was?

I am less sure of the answer after our recent work at the Great Aten Temple. What is emerging is evidence, in the shape of small platforms surrounded by troughs intended to be filled with water, for which one can offer the interpretation that they were for the preparation of the dead. The idea is far from provable and has to stand as a hypothesis. But from the late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties come several tomb pictures at Thebes and Saqqara of places where the ceremonies for the dead were performed on islands surrounded by water and by numerous offering-tables. The offerings were for the benefit both of the spirits of the dead. Thus the many offering-tables at the Great Aten Temple could have been for the benefit both of the Aten itself and for the spirits of the recently dead at Amarna. But we are still at the early stages of exploring the ground which surrounds the temple.

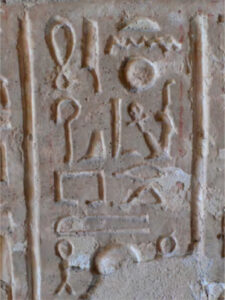

We know that during the reign of Horemheb, they started the demolition and dismantling of the buildings of Akhetaton, whose materials were reused in the new structures that were rising in nearby towns, especially in Hermopolis. However, in Akhetaton was found an ostracon inscribed with the cartouches of Horemheb and Seti I. Also, in 1922 archaeologists uncovered buildings and debris that were more recent than the reign of Akhenaten. They also discovered traces of what could be a small sanctuary where appears the name of Horemheb in the precincts of the Great Temple of Aton. These are obvious signs of the occupation of the city, or part of it, and therefore it seems that the general belief that Amarna was abandoned after the fall of Akhenaten’s reign is not correct. So – why on one hand did they want to dismantle the city of the Pharaoh considered heretical and, on the other, they built other sanctuaries leaving evidence that life and religious activities continued to be exercised?

The Horemheb evidence (the first piece to be found was a block by the Petrie/Carter expedition of 1891/2) amounts to very little and could have been a single small shrine honouring Horemheb himself, put up as the serious demolition of the Great Aten Temple began. At the far southern end of the city, where stands the modern village of el-Hagg Qandil, occupation continued through to late in the New Kingdom and perhaps beyond. This was established in 1922 by the EES excavation of the ‘River Temple’ site which was, in fact, an area of housing of the late New Kingdom or even later. The village or small town was there probably because it served the quarries at Harnub.

The abandonment of the greater part of Amarna is likely to have had two aspects. One was the drastic reduction of its population, except at its southern end. The demolition of the stone buildings would have required labourers but they might have set up rudimentary camps amongs the stone ruins themselves. The Horemheb/Sety I ostracon (which cannot be located now and is known only from photographs and the brief comment in JEA) was found not so far from the Central City and does, indeed, imply that people were still living in houses in that area although they are otherwise undetectable. The city would also have lain open to people scavenging for reusable materials and buried treasured.

The other aspect was the decision (nowhere recorded but inevitable) to withdraw the main administrative apparatus from Amarna, thus the archives and the stores of commodities and manufactured goods held in extensive storerooms. The most likely time for this is early in the reign of Tutankhamun. Once this had been done, and the top tier of administrators had left, much of the population is bound to have left also since so many people must have been dependent in one way or another on senior officialdom.

What is the finding, or set of findings, that you feel more attached to? And why?

I am attached to the way that, over the years and sometimes through circumstances outside my control, the expedition has worked over a wide variety of types of site at Amarna. As a result we have amassed evidence for different facets of the city. By comparing them – in effect by cycling repeatedly through them – one has the best chance of gaining a better understanding of what it all means. The addition in recent years of material from the cemeteries of ordinary people has been a particular boost.

Do you think that the Arab Spring has somewhat hampered your research? If so, how? What do you see as the future for your excavation plans in Egypt?

Throughout this time the Ministry of Antiquities has continued to function and to process the applications of foreign expeditions in the normal way. Expeditions also, however, require the agreement of the local security authorities. For two periods of around two or three months (in early 2011 and the autumn of 2014) this agreement was not forthcoming and work was postponed. The Ministry of Antiquities continues to regard foreign expeditions positively and I hope we are able to continue, long into the future, to renew our annual permit to work at Amarna.

Your studies focus more on the city of Akhenaton rather than on its inhabitants, but through your research you must have formed some ideas about the people that lived there. For example, what do you think of Akhenaten? Some see him as a dictator, a tyrant, a man of few scruples ready to do anything to achieve his goals. Others see him as an enlightened romantic. What is your view?

Authority in past societies was generally firm to the point of being brutal. I do not see that we have the basis for judging whether Akhenaten was more or less so than other Pharaohs. It is also virtually impossible to know to what extent his ideas and plans carried the support of the official class, to what extent he represented a broader awakening of consciences. In the longer term, those who benefited from the ending of his family’s rule were the military but we have no way of knowing if they actively undermined his plans. I am sure he was driven by a personal vision which drew strength from dissatisfaction with the way things were. But we have little that is in his own words. The Aten itself as a source of power did not suffer subsequent rejection. It appears in later sources as a component of the knowledge of where ultimate divine power lay. What was rejected was Akhenaten’s eccentric style of rule, but again we do not know how extensive his eccentricities were.

Jan Assmann believes that Akhenaten destroyed the concept of Maat, on which Egypt was built. He thinks that this was the cause for his religion not lasting beyond his reign. We know that the Akhenaten associates his figure with the idea of justice and order, replacing Maat by identifying himself with it. He is now the one who interprets their desires and offers himself to God. He acts as the only intermediary to Aton and without nominating any successor to exercise this function after his death. So when he died, also the only intermediary with God died. So, there were no more rulers. It’s easy to understand that, disoriented and bewildered, the people of Amarna and all those faithful to the new religion would return to the old cults. Why is it that such a clever Pharaoh like Akhenaten never thought about this and never considered the danger of the clergy of Amon? What could Akhenaten have done to prevent the death of his religion after his own death?

do not understand the reasoning. In many ways Maat was promoted as a major concept at Amarna and clearly as the arbiter of good and just conduct. In the tomb of Ay, the Aten is said to be the ‘Prince of Maat’, her name written using the traditional determinative of the seated goddess wearing the maat-feather. The eastern desert was the ‘place of Maat’. Akhenaten repeatedly states that he ‘lived on Maat’, as if it were his food. His courtiers praised him for helping them to distinguish Maat from its opposite. I see this evidence as pointing to Akhenaten as a teacher of what adherence to Maat really meant. Rather than destroying it, I would see the evidence as pointing to Akhenaten promoting Maat more fervently than ever.

We have only the Boundary Stelae to tell us what was in Akhenaten’s mind. They limit his intentions to the foundation of Akhetaten. All that he did – so he tells us – was for the benefit of the Aten. Once Akhetaten had been created, Akhenaten had fulfilled the vision that he gives us in those texts. I have often wondered if a moment came when, realising that he had done what he set out to do, he thought of something further. Or was he then content just to rule in his own inimitable style? I do not know.

We do not know if Akhenaten refrained from nominating a successor. We can only see the history of the period through the reliefs and carved texts. The people themelves will have witnessed it and participated in it as part of a society of living and very active individuals, a very different experience. The modern debates on the subject reveal all too clearly that what actually happened was mostly not made the subject of monumental record. But I see no reason to think that Ankh-kheperura Smenkhkara was not the nominated successor, married (logically enough) to Meretaten. Explanations which seek to avoid this conclusion seem to me to be perverse.

Nefertiti: beautiful and charismatic, always by the side of her husband at official ceremonies both public and religious as well as being a skillful diplomat. What was her role before, during and after the reign of Akhenaten?

Being beautiful does not necessarily mean that the person is charismatic, a characteristic that is hard to define. In the case of Nefertiti we have to rely upon sources which were chosen to have a particular effect. We have no alternative sources. But do note that at Amarna itself Meretaten seems, at least in some circumstances, to have had greater prominence in the latter part of Akhenaten’s reign and this was recognised by foreign rulers in some of the letters they wrote to the Egyptian court. One explanation is that she was put in charge of Akhenaten’s household at Amarna.

Amarna art includes countless representations of private life at Court, scenes suffused with love and affection, both within the couple and the family. Why, given the amount of material available, has the subject never inspired a book about the love story between Akhenaten and Nefertiti?

Has it not? I am not the person to ask. I am deeply interested in the history of ideas and of processes, much less in the history of individuals where one has to rely largely upon invention to make up for the lack of sources. One can take the view that, in the end, all human beings are likely to behave in similar ways and therefore it is justified, with a bit of empathy, to write a family saga about any group from the past. But then, why bother? You will realise from this that I do not read much historical fiction.

Before arriving at Amarna, you worked with the University of Pennsylvania at the royal palace and the city of Amenhotep III in Malqata. Let’s talk about Teye, wife of Amenhotep III and mother of Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten. She was present in both reigns and during the co-regency. How strong do you think her influence was during her son’s reign?

If you believe that a person’s character can be read from their face, then Teye is a good ancient Egyptian to work with. Her statue heads invite the interpretation that she was the archetypal strong mother/mother-in-law. But if you think that such an approach is wishful thinking (as I do) then you are left with nothing to work with.

What’s your view on Nicholas Reeves’s recent theory according to which Tutankhamen’s tomb conceals other chambers and possibly even Nefertiti’s tomb?

Reeves has drawn attention to what he sees as anomalies in some of the wall surfaces in the tomb, as revealed by recent 3D scanning. There is nothing further to do other than to hope that the actual walls will be subjected to non-destructive investigation by sensing equipment. Since one is checking for doorways cut into limestone and probably filled with blocks of the same material, sensing might not give clear results. Nevertheless, from press releases the Ministry of Antiquities is taking Reeves’ claim seriously and is considering an investigation.

All we can reasonably do is to wait and see. The most valuable discovery would be a written document which gave us contemporary comment on what was happening in Egypt. Was the Amarna Period primarily one individual’s ego-trip or was Akhenaten articulating a wider debate about fundamental ideas, including public morality?

Italian version of this post:

https://mediterraneoantico.it/articoli/egitto-vicino-oriente/intervista-a-barry-john-kemp/

Info: www.amarnaproject.com