14

The workers' village of Akhetaton is very close in time to Deir el-Medina. Analyzing the site

and its findings concerning the daily life of the workers, the hours that marked their days, the

construction of their homes, customs, etc. etc., did you find evidence that suggests more

differences, or similarities? And how about with that of Giza?

Comparison with Deir el-Medina illustrates the elusive nature of the goal of reconstructing

ancient life from archaeology. Most of what we know of the life of the Deir el-Medina commu-

nity comes from texts: the ostraca and occasional papyri. Papyrus generally does not survive

well, even in the desert, and

has been an excessively

rare find at Amarna. The

widespread

use

of

potsherds and flakes of li-

mestone as writing mate-

rials was a peculiarity of

Ramesside Deir el-Medina,

not matched elsewhere in

the New Kingdom, inclu-

ding at Amarna. If one were

to remove the written ma-

terial from Deir el-Medina

and rely wholly upon its ar-

chaeology the result would

be a much impoverished

picture (as is true for Deir

el-Medina itself for the

Eighteenth Dynasty). The

Deir el-Medina evidence of-

fers powerful and intri-

guing possibilities for un-

derstanding the Amarna

Workmen’s Village. Yet one has to hesitate before assuming that the two places worked in the

same way. If we had for Amarna the same wealth of written evidence, by now an important

question would be to investigate how far Amarna adapted to changed circumstances and

how far it kept to long-established practices.

As for the Old Kingdom town at Giza, it is so different from Amarna and itself lacks adequate

written sources that comparison can only be done at a general level. At the same time, the

twenty-five years that Mark Lehner has spent directing work there has provided the only set of

data for a large settlement from ancient Egypt which is comparable to Amarna. We (the

Amarna Project group) have not yet looked closely enough at the comparisons which can be

made.

The hundreds of tables of offerings found within the sacred enclosures and temples seem

almost an obsession given their large number. Why do you think this was?

I am less sure of the answer after our recent work at the Great Aten Temple. What is emerging

is evidence, in the shape of small platforms surrounded by troughs intended to be filled with

water, for which one can offer the interpretation that they were for the preparation of the

dead. The idea is far from provable and has to stand as a hypothesis. But from the late Eighte-

enth and Nineteenth Dynasties come several tomb pictures at Thebes and Saqqara of places

where the ceremonies for the dead were performed on islands surrounded by water and by

numerous offering-tables. The offerings were for the benefit both of the spirits of the dead.

Thus the many offering-tables at the Great Aten Temple could have been for the benefit both

of the Aten itself and for the spirits of the recently dead at Amarna. But we are still at the early

stages of exploring the ground which surrounds the temple.

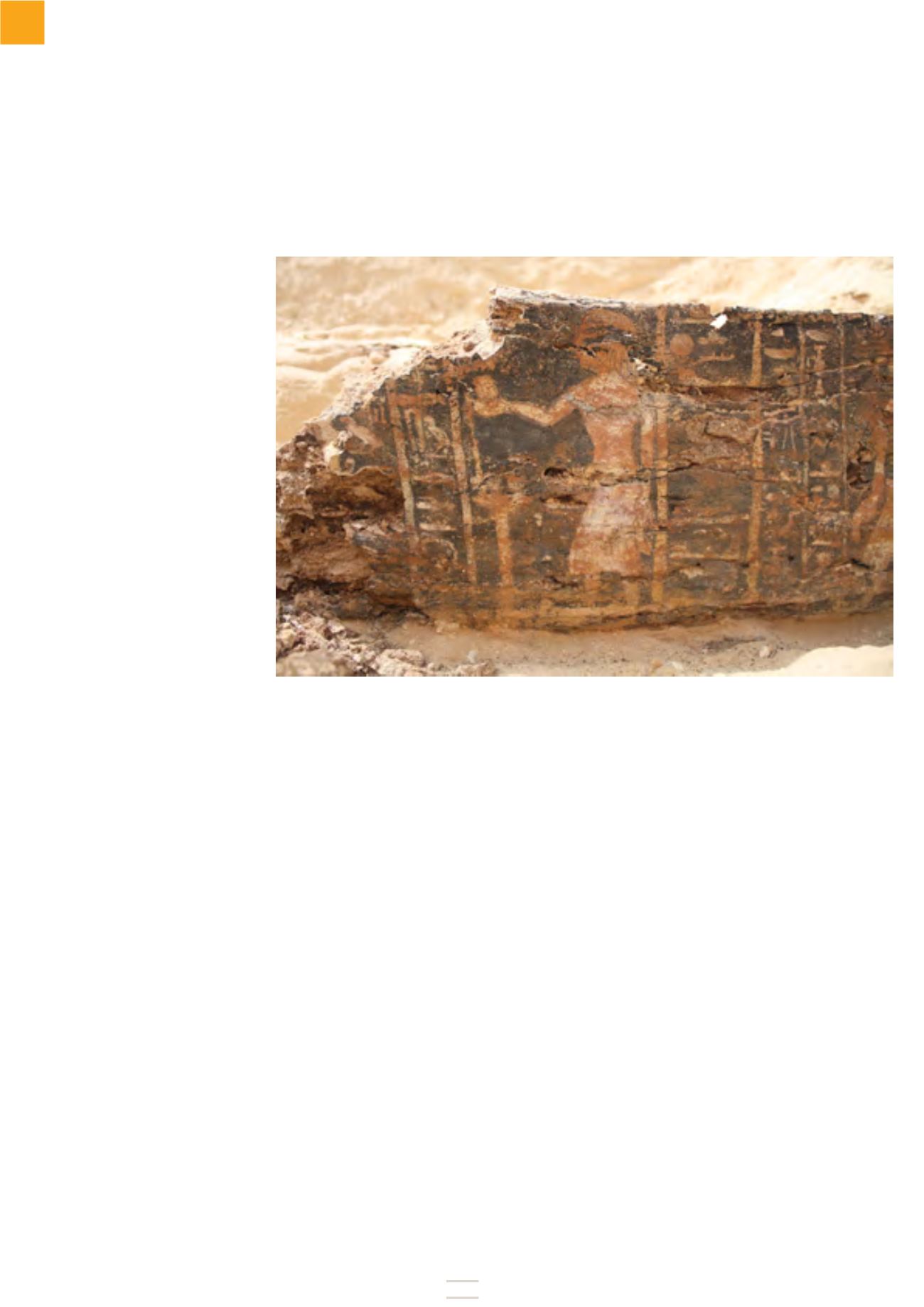

The side of a decorated wooden coffin from the South Tombs Cemetery. The layout of the decoration is traditional

but the usual figures of protective gods have been replaced by human offering-bearers.